Avoiding Holiday Heart Syndrome

Local cardiologists explain the risks, symptoms, and simple steps to stay healthy during the holidays.

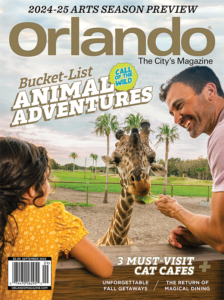

Overindulging in food and drink during the holiday season could lead to holiday heart syndrome. (ROBERTO GONZALEZ)

Despite its seemingly festive name, “holiday heart syndrome” (HHS) can cause the heart to race or pound in a frightening manner—usually after over exuberant partying with food and drink, physicians say.

This heart condition “could be better named, perhaps,” concedes Dr. Mahmoud Altawil, a cardiologist and clinical cardiac electrophysiologist at AdventHealth in Orlando. “But it’s catchy and serves its purpose well,” drawing attention to atrial fibrillation (AFib), the most common heart rhythm disorder, which doctors frequently see between Thanksgiving and New Year’s when people overindulge, especially with alcohol.

Most holiday revelers who develop these sudden electrical disturbances inside the heart do fine, as symptoms sometimes resolve on their own, Dr. Altawil says. Still, AFib, if undiagnosed or left untreated, can lead to serious heart issues. Many studies have shown that persistent atrial fibrillation carries a five times greater risk for stroke, while the chaotic rhythm disruptions in the heart’s two upper chambers, known as the atria, cause structural damage that weakens the heart over time, leading to heart failure.

The American Heart Association estimates that at least 2.7 million Americans today are living with atrial fibrillation. How many were first diagnosed with holiday heart syndrome is uncertain.

“It’s difficult to pinpoint—perhaps 5 percent to 10 percent tops, in any given year,” says Dr. Roland Filart, a clinical cardiac electrophysiologist specializing in treating the heart’s electrical disturbances, who works at Orlando Health Heart & Vascular Institute. He says no matter the exact percentage, physicians know the syndrome’s dominant trigger is too much alcohol, which can open a “Pandora’s box” of problems threatening the heart, not just during the holiday season but all year round.

However, how much alcohol is too much remains ill-defined and varies according to each individual’s alcohol tolerance. One drink might be enough to disturb one person’s natural heart rhythm, yet in another, it might take many drinks. Surprisingly, many patients diagnosed with holiday heart syndrome apparently have no history of heart disease or barely notice any heart-distressing irregularities before showing up for treatment in urgent care centers or the emergency room.

“There’s a big individual component in atrial fibrillation, based on the data,” Dr. Altawil says. “Everybody knows their own body best.” Whether to wait it out or rush to the ER for immediate medical care depends on how each person perceives the severity of their symptoms. If a person is experiencing symptoms similar to a heart attack, such as chest pains, shortness of breath, or even a general sense of unease, Altawil says it never hurts to get checked out, especially if any of these symptoms seem new.

“If someone’s heart is beating too fast and they’re worried about a heart attack, it’s a good idea to come in,” Dr. Filart agrees. “Otherwise, if their symptoms seem minor and they’re feeling fine, they can wait and go to the doctor the next day.”

They define a rapid heart rate as anything over 100 beats per minute. But that number must be considered in context.

“During running or other exercises, that could be a normal heart rate,” Dr. Filart says, with an EKG confirming an abnormal rhythm only when symptoms occur “right then and there.” Sometimes these rhythm disturbances come and go quickly, while at other times, they last for years.

Still, both cardiologists stress that holiday heart syndrome usually goes away on its own after the individual rests and abstains from further alcohol use. They encourage risk modification strategies first.

Patients with confounding health issues can worsen an episode of holiday heart syndrome. These health issues include diabetes, high blood pressure, or undiagnosed sleep apnea. But, many available drugs exist that can slow the heart rate, thin the blood to reduce the clotting risk or tame the electrical impulses responsible for the heart’s impairment. If symptoms persist, most are highly manageable.

In addition, there are medicines to chemically restore orderly contractions and normal blood flow between the atrium and the heart’s ventricles or lower chambers as the heart muscle contracts to pump oxygenated blood throughout the body. Doctors can even shock the heart back to normal through cardioversion.

Ultimately, the approach doctors use depends on many factors, not least of which is the acuity of the situation. A few months ago, Dr. Filart treated a football coach who came into the hospital severely dehydrated and stressed after winning a local football championship. Because his heart rate was so high at the time, posing an imminent stroke risk, the team immediately performed cardioversion by shocking his heart back to normal using paddles placed on each side of his chest. “We had to get him out of AFib quickly or risk losing him,” Dr. Filart explains.

In comparison, a second patient experiencing a less extreme abnormal heart rhythm needed less aggressive treatment. He wandered into the hospital feeling poorly after celebrating a golf win with his buddies, says Dr. Filart. The patient’s condition improved quickly so the medical team gave him a beta-blocker to slow his racing heartbeat and sent him home for a later follow-up.

Both cases illustrate the complexity of AFib and its role in contributing to heart disease. Because advancing age—65 and older—increases the risk, the Centers for Disease and Prevention now predicts the number of Americans diagnosed with atrial fibrillation by 2030 could climb as high as 12.1 million—underscoring the need for better awareness.

If the term holiday heart syndrome misleads people into thinking, “this might be referring to a good thing,” that couldn’t be further from the truth. AFib is far from positive, but Dr. Altawil looks on the good side. “It could encourage patients to learn more about it.”